Across Vietnam, portable mini fans, wireless earphones, and rechargeable power banks—once hailed as symbols of energy-efficient green technology—are piling up in landfills, threatening soil, water, and public health. With the country discharging over 90,000 tonnes of electronic waste annually, the environmental cost of these cheap, short-lived gadgets is becoming impossible to ignore. As global e-waste is projected to reach 74 million tonnes by 2030, according to the World Health Organization (WHO), Vietnam faces an urgent question: can technology truly be green if it leaves behind a toxic legacy?

The Hidden Cost of Convenience

In the sweltering heat of Vietnam’s summer, portable mini fans are ubiquitous, whirring in offices, schools, and public spaces. Marketed as eco-friendly for their use of clean energy, these devices are often purchased for as little as 80,000 Vietnamese Dong (~US$3.15) on e-commerce platforms. Yet, their low cost belies a grim reality: when they break after just a few months, most are tossed into household waste bins, contributing to a growing environmental hazard.

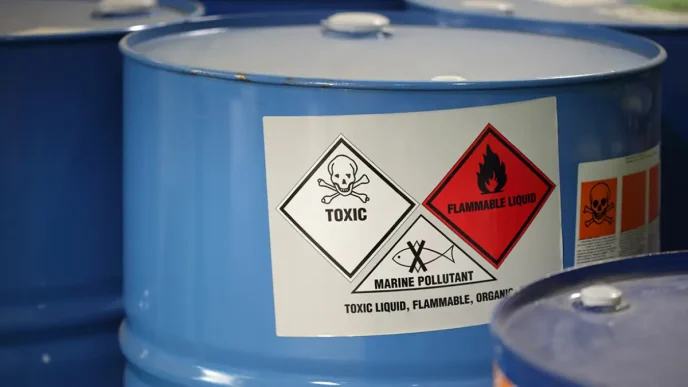

The problem lies in the design and materials of these gadgets. Many, including mini fans and portable chargers, rely on lithium-ion batteries, which store high energy but are notoriously difficult to decompose. If not properly treated, discarded batteries can ignite, explode, or leak toxic chemicals like cadmium, lithium, and mercury into soil and water. The consequences are dire, with pollution threatening ecosystems and human health alike.

Nguyễn Văn Hùng, an office worker in Hanoi, encapsulates a common consumer mindset. “I bought a portable rechargeable fan for a very low price. It broke after a few months of use”, he told a local news outlet in 2025. “It’s too costly to repair, so I threw it away and bought a new one.” Hùng’s approach—discarding rather than repairing—is not unique. Cheap green tech gadgets, often from unbranded manufacturers, are typically of poor quality, break quickly, and are uneconomical to fix.

Recycling Challenges and Systemic Failures

The disposal of these devices is compounded by Vietnam’s limited recycling infrastructure. Trần Văn Nam, who runs a recycling facility in Hanoi, highlighted the difficulties in handling small electronic devices. “Separating lithium-ion battery panels from small devices is very difficult and costly because it requires high technology. Therefore, many small-scale recycle workshops just disassemble them for copper and then dump or burn the broken devices” he explained in a recent interview. As a result, many small-scale recycling workshops simply extract valuable materials like copper and then dump or burn the remaining components, further exacerbating pollution.

Currently, Vietnam has only about 15 licensed facilities for electronic waste recycling, each with a capacity of just 0.5 to 3 tonnes per day. This modest capability not only misses the opportunity to recover precious materials like gold and lithium but also fails to mitigate the environmental fallout. Without a specialized collection system, much of the country’s e-waste ends up in landfills or is improperly handled by informal recyclers.

Environmental experts point to a deeper issue: a lack of accountability across the supply chain. The influx of cheap tech products, often imported through unofficial channels by small-scale sellers, prioritizes profit over post-sale responsibility. These sellers operate within a linear economic model—produce, consume, discard—leaving urban authorities and residents to bear the burden of waste management. “Those who cause environmental pollution should pay for its treatment” argue experts, yet the costs are often absorbed by the state budget, funded by taxpayers.

The Responsibility Gap

A critical barrier to addressing Vietnam’s e-waste crisis is the responsibility gap among manufacturers, importers, and distributors. Many of these entities, particularly those dealing in low-cost, no-name products, evade accountability for the lifecycle of their goods. This inequality in cost allocation means that while businesses profit, society pays the price for environmental degradation.

Under Vietnam’s Law on Environmental Protection, provisions for Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) mandate that businesses manufacturing or importing potentially polluting products—such as batteries and electronic devices—must contribute to their collection and recycling. However, enforcement remains a challenge, especially for unbranded or low-cost items. Lawyer Bùi Đình Ứng noted that while the legal framework exists, “enforcing this regulation on low-cost technology products, often without clear brands, faces numerous difficulties.”

Without stronger regulations to compel compliance, manufacturers and importers lack the incentive to design environmentally friendly products or establish take-back programs. The absence of such initiatives perpetuates a cycle of waste, with discarded gadgets piling up in communities ill-equipped to handle them.

Paths to a Sustainable Future

Addressing Vietnam’s e-waste crisis requires a multi-pronged approach. First, expanding collection points for hazardous electronic waste in residential areas, supermarkets, and shopping centers is essential to ensure proper disposal. Such infrastructure would provide accessible options for consumers like Hùng, who currently have few alternatives to throwing broken devices into household waste.

Second, businesses must be held accountable through stricter enforcement of EPR rules, regardless of their size or market share. Policies could mandate that environmental treatment fees be factored into production costs, incentivizing companies to adopt sustainable practices. Take-back programs, such as exchanging old products for subsidized new ones, could not only reduce waste but also build customer loyalty and enhance brand reputation.

Finally, a shift toward a circular economic model—where products are designed for reuse, repair, or recycling—offers a long-term solution. This would require collaboration between government, industry, and consumers to rethink how technology is produced and consumed. For Vietnam, a country grappling with rapid urbanization and increasing tech adoption, such a transformation is not just desirable but necessary.

A Global Problem with Local Impacts

Vietnam’s struggle with e-waste is part of a broader global challenge. The WHO’s forecast of 74 million tonnes of electronic waste by 2030 underscores the urgency of addressing this issue worldwide. Yet, the impacts are acutely felt at the local level, where communities bear the brunt of pollution and health risks. In Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh City, the sight of discarded mini fans and power banks in trash heaps is a stark reminder of the hidden costs of convenience.

Consumer habits also play a role. The preference for cheap, disposable gadgets over durable, repairable alternatives fuels the waste stream. Education campaigns could shift public attitudes, encouraging more responsible purchasing and disposal practices. However, without systemic change—particularly from producers and policymakers—individual efforts will fall short.

Looking Ahead

As Vietnam navigates the intersection of technological advancement and environmental sustainability, the e-waste crisis serves as a critical test of its policies and priorities. Stronger regulations, improved infrastructure, and a commitment to corporate responsibility are essential to prevent green technology from becoming a misnomer. The question remains: will the country rise to the challenge, or will the burden of toxic waste continue to weigh on future generations?