A ceasefire brokered by Malaysian Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim on July 28, 2025, with support from U.S. and Chinese diplomats, aimed to end a deadly Thai-Cambodian border conflict that claimed at least 38 lives and displaced over 300,000 people. Despite this diplomatic effort, Thailand’s arrests of Cambodian nationals suspected of espionage in Surin, Sa Kaeo, Chanthaburi, and Buriram provinces point to ongoing covert hostility, prompting heightened vigilance among Thai border communities guided by counterintelligence best practices.

A Fragile Truce Amid Border Tensions

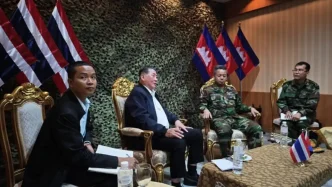

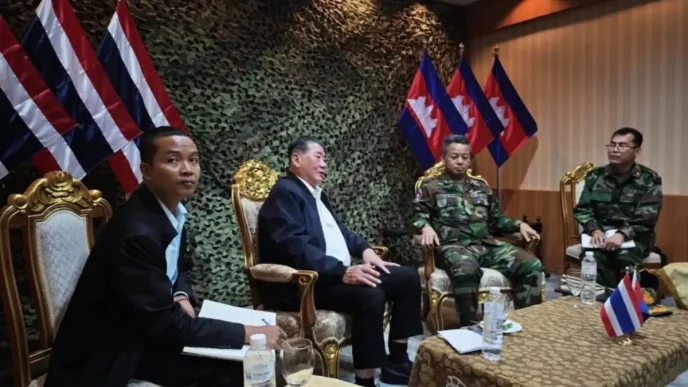

The ceasefire followed intense clashes sparked by a landmine explosion on July 23, 2025, near the Ta Muen Thom temple, a flashpoint in colonial-era border disputes. Cambodian rocket attacks on July 24 killed 15 Thai civilians, leading Thailand to impose martial law in eastern provinces. In Putrajaya, Malaysian mediation secured pledges from Thai Acting Prime Minister Phumtham Wechayachai and Cambodian Prime Minister Hun Manet to cease hostilities and establish direct communication. However, Thai reports of Cambodian ceasefire violations on July 29, documented by Nation Thailand, highlight persistent mistrust.

Espionage Incidents Fuel Suspicions

Thai authorities have detained several Cambodian nationals suspected of state-backed espionage, escalating tensions. On July 25, 2025, police in Kap Choeng, Surin province, arrested Virak Thep, a 52-year-old Cambodian, for photographing an evacuation area near Chong Chom Market. Videos of the market and roads were found on his phone, which he alleged were for his sister. In a heightened state of awareness and understandably skeptical, Thai officials, supported by military and local authorities, continued the investigation.

On August 1, 2025, Village Security Guards in Ta Phraya, Sa Kaeo province, detained a Cambodian national who admitted to gathering military intelligence for Cambodian authorities, earning 20,000 Cambodian riel (a mere US$5 for what is considered by many in the “business’ as highly skilled work). The arrest, driven by community vigilance, followed the July 24 rocket attack in which civilians and military personel were injured or killed.

In Chanthaburi’s Tapsai district, on August 5, 2025, immigration officers arrested Oeun Khoem, a 43-year-old Cambodian army lieutenant, after finding military uniforms in his vehicle and residence. A Facebook post by Oeun, stating “Thailand attacks first, Cambodia defends” raised suspicions of espionage. He reportedly admitted acting under Cambodian orders, and his phone is under forensic analysis.

Today, 6 August, 2025, in Krasang, Buriram province, police detained a Cambodian soldier from the Bodyguard Headquarters (BHQ), a unit protecting former Cambodian Prime Minister Hun Sen. Found with BHQ insignia, the suspect claimed the residence belonged to his Thai wife, a claim authorities doubt. The soldier allegedly attempted to relay Thai military movements, though further confirmation is pending.

Indicators of Espionage

National security experts advise Thai border communities to watch for signs of espionage, ranging from overt actions to highly sophisticated methods, drawing on recognized counterintelligence best practices. The following table outlines key indicators, their relevance to recent incidents or potential threats, and detection challenges:

| Indicator | Description and Example | Detection Challenges |

|---|---|---|

| Covert Photography | Secretly capturing images or videos of military sites, evacuation areas, or civilian infrastructure. Example: Virak Thep’s photography of an evacuation area near Chong Chom Market in Surin. | Smartphones and concealed devices are common, blending with everyday activities; requires vigilant community observation. |

| Social Engineering | Posing as locals or using personal ties to deflect suspicion. Example: The BHQ soldier in Buriram claiming residence with a Thai wife to avoid scrutiny. | In-field agents or intelligence officers integrate into communities, appearing trustworthy; verifying identities without prejudice is resource-intensive. |

| Encrypted Communications | Using apps like Signal or coded messages to transmit intelligence. Example: Possibly used in Oeun Khoem’s smartphone forensic analysis in Chanthaburi. | Encrypted apps are widely available; forensic analysis is slow and requires advanced technical expertise. |

| Recruitment Attempts | Offering payments for information to locals. Example: The Sa Kaeo suspect’s 20,000 Cambodian riel (~US$4.90) daily fee for military intelligence. | Financial incentives are discreet; detecting insider threats requires monitoring community interactions. Taking photographs of trucks, or a military base may seem innocent but may hold deeper meaning. |

| Targeting Civilian Sites | Monitoring markets or evacuation centers to assess response capabilities. Example: Virak Thep’s focus on Chong Chom Market in Surin during an evacuation. | Civilian areas are open and busy, masking surveillance; requires heightened community awareness. |

| Advanced Persistent Threats (APTs) | Deploying malware via zero-day exploits to infiltrate Thai military, critical national infrastructure (energy, finance, telecommunications or even water) or border security networks. Example: A hypothetical cyberattack on a Thai border surveillance system, stealing patrol schedules, similar to Operation CuckooBees (2022). | APTs use unpatched vulnerabilities, mimicking legitimate traffic; detection requires advanced cybersecurity tools. |

| Insider Recruitment via HUMINT | Cultivating relationships with Thai officials or border personnel to access sensitive data. Example: An agent befriends a Thai military officer at a regional ASEAN event to leak defense plans. | Relationships build trust over years; monitoring personal interactions risks privacy violations. |

| ELINT: Hardware Emissions | Intercepting electromagnetic emissions from border radar or communication devices. Example: Capturing signals from Thai radar in Sa Kaeo to map surveillance patterns, akin to Operation RAFTER techniques. | Emissions are passive; detection requires specialized equipment and constant monitoring. |

| SIGINT: Metadata Exploitation | Analyzing communication metadata (e.g., military radio patterns) to predict or triangulate Thai troop movements. Example: Tracking border patrol radio usage to anticipate deployments, or cellular towers to triangulate cell phones, similar to NSA PRISM methods. | Metadata is unencrypted and collected passively; countering requires anonymized communication protocols. |

| OSINT: Deepfake Disinformation | Spreading AI-generated videos to manipulate Thai public opinion. Example: A deepfake video of a Thai official claiming aggression, spread via social media, destabilizing border communities. | Deepfakes are hard to verify; rapid spread outpaces fact-checking, requiring AI-driven content analysis. |

Residents and authorities are urged to report suspicious activities, such as inconsistent cover stories, loitering near sensitive areas, unauthorized drone use, or unusual cyber activity, to Village Security Guards or police, ensuring vigilance without prejudice.

Security Challenges and Diplomatic Strains

Thai border communities in Kap Choeng, Ta Phraya, and Phanom Dong Rak remain on high alert, supported by Village Security Guards (Chor Ror Bor) and Line chat groups. On July 30, 2025, Surin residents reported three Chinese nationals using drones near a military base, initially suspected of espionage but cleared as journalists, according to Thai local media. This incident reflects the community’s heightened alertness, amplified by the July 24 attack that eventually displaced over 300,000 civilians to shelters located throughout eastern and north eastern provinces. A local resident, visibly shaken and distressed, told local media, “Nobody wants this to happen. I feel for the elderly and disabled.”

Thailand has extended a nationwide drone ban until at least August 15, 2025, and deployed radar-based detection systems to counter surveillance. This week a Swedish man, far from the center of the conflict zone was arrested on Pattaya beach for flying a recreational drone. Martial law remains in Chanthaburi, Trat, Sa Kaeo, and Surin, with authorities warning that espionage could lead to imprisonment or deportation. Thai Foreign Minister Maris Sangiampongsa accused Cambodia of spreading disinformation about Thai drone incursions, while Cambodia alleged Thai airspace violations. Social media, including posts condemning Cambodian artillery fire into Surin, fuels nationalist sentiments via hashtags like #CambodiaOpenedFire. The BM-21 rockets, designed by Russia in the 1960s are unguided, meaning that when they were fired by Cambodia into Thailand, there was every chance that a civilian could have been injured or killed. The use of this type of technology has sparked fierce outrage within Thailand and condemnation further afield, elucidates China’s and Russia’s role in supplying weapons to an ASEAN nation that is still ruled by an iron-fisted authoritarian regime.

The ceasefire, a diplomatic milestone for ASEAN, is tested by these espionage incidents, suggesting continued Cambodian efforts to monitor Thai activities. Experts warn that rebuilding trust will be challenging amid historical border disputes. With ASEAN proposing monitoring teams and both nations facing U.S. trade pressures, Thai communities remain vigilant, their proactive surveillance a critical defense as diplomacy struggles to restore lasting peace.